BIP: ?

Title: Schnorr Signatures for secp256k1

Author: Pieter Wuille <[email protected]>

Status: Draft

Type: Informational

License: BSD-2-Clause

Post-History: 2018-07-06: https://lists.linuxfoundation.org/pipermail/bitcoin-dev/2018-July/016203.html [bitcoin-dev] Schnorr signatures BIP

This document proposes a standard for 64-byte Schnorr signatures over the elliptic curve secp256k1.

This document is licensed under the 2-clause BSD license.

Bitcoin has traditionally used

ECDSA signatures over the secp256k1 curve for authenticating

transactions. These are standardized, but have a number of downsides

compared to Schnorr signatures over the same curve:

For all these advantages, there are virtually no disadvantages, apart

from not being standardized. This document seeks to change that. As we

propose a new standard, a number of improvements not specific to Schnorr signatures can be

made:

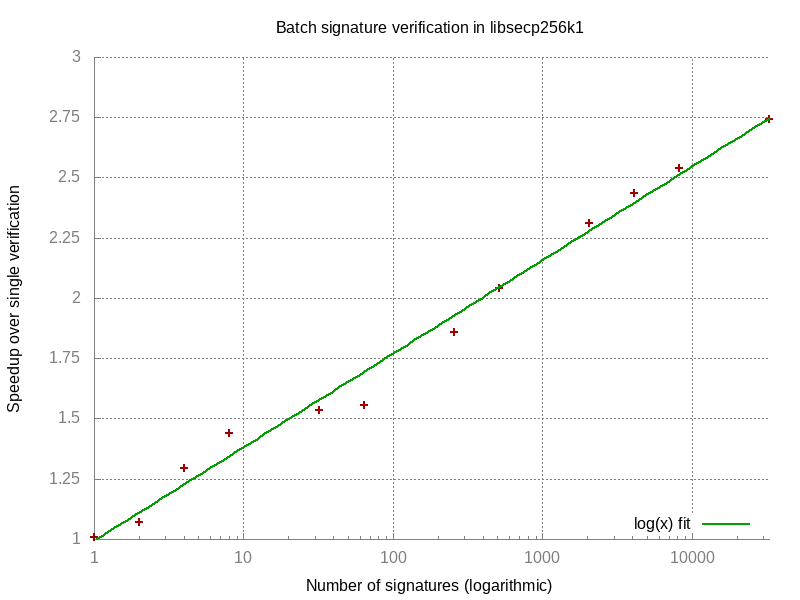

This graph shows the ratio between the time it takes to verify n signatures individually and to verify a batch of n signatures. This ratio goes up logarithmically with the number of signatures, or in other words: the total time to verify n signatures grows with O(n / log n).

By reusing the same curve as Bitcoin has used for ECDSA, private and public keys remain identical for Schnorr signatures, and we avoid introducing new assumptions about elliptic curve group security.

We first build up the algebraic formulation of the signature scheme by

going through the design choices. Afterwards, we specify the exact

encodings and operations.

Schnorr signature variant Elliptic Curve Schnorr signatures for message m and public key P generally involve a point R, integers e and s picked by the signer, and generator G which satisfy e = H(R || m) and sG = R + eP. Two formulations exist, depending on whether the signer reveals e or R:

(e,s) that satisfy e = H(sG - eP || m). This avoids minor complexity introduced by the encoding of the point R in the signature (see paragraphs “Encoding the sign of R” and “Implicit Y coordinate” further below in this subsection).(R,s) that satisfy sG = R + H(R || m)P. This supports batch verification, as there are no elliptic curve operations inside the hashes.We choose the R-option to support batch verification.

Key prefixing When using the verification rule above directly, it is possible for a third party to convert a signature (R,s) for key P into a signature (R,s + aH(R || m)) for key P + aG and the same message, for any integer a. This is not a concern for Bitcoin currently, as all signature hashes indirectly commit to the public keys. However, this may change with proposals such as SIGHASH_NOINPUT (BIP 118), or when the signature scheme is used for other purposes—especially in combination with schemes like BIP32’s unhardened derivation. To combat this, we choose key prefixed2 Schnorr signatures; changing the equation to sG = R + H(R || P || m)P.

Encoding the sign of R As we chose the R-option above, we’re required to encode the point R into the signature. Several possibilities exist:

Using the first option would be slightly more efficient for verification (around 5%), but we prioritize compactness, and therefore choose option 3.

Implicit Y coordinate In order to support batch verification, the Y coordinate of R cannot be ambiguous (every valid X coordinate has two possible Y coordinates). We have a choice between several options for symmetry breaking:

The third option is slower at signing time but a bit faster to verify, as the quadratic residue of the Y coordinate can be computed directly for points represented in

Jacobian coordinates (a common optimization to avoid modular inverses

for elliptic curve operations). The two other options require a possibly

expensive conversion to affine coordinates first. This would even be the case if the sign or oddness were explicitly coded (option 2 in the previous design choice). We therefore choose option 3.

Final scheme As a result, our final scheme ends up using signatures (r,s) where r is the X coordinate of a point R on the curve whose Y coordinate is a quadratic residue, and which satisfies sG = R + H(r || P || m)P.

We first describe the verification algorithm, and then the signature algorithm.

The following convention is used, with constants as defined for secp256k1:

p refers to the field size, 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFEFFFFFC2F.n refers to the curve order, 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFEBAAEDCE6AF48A03BBFD25E8CD0364141.y<sup>2</sup> = x<sup>3</sup> + 7 over the integers modulo p.

infinite(P) returns whether or not P is the point at infinity.x(P) and y(P) are integers in the range 0..p-1 and refer to the X and Y coordinates of a point P (assuming it is not infinity).G refers to the generator, for which x(G) = 0x79BE667EF9DCBBAC55A06295CE870B07029BFCDB2DCE28D959F2815B16F81798 and y(G) = 0x483ADA7726A3C4655DA4FBFC0E1108A8FD17B448A68554199C47D08FFB10D4B8.|| refers to byte array concatenation.x[i:j], where x is a byte array, returns a (j - i)-byte array with a copy of the i-th byte (inclusive) to the j-th byte (exclusive) of x.bytes(x), where x is an integer, returns the 32-byte encoding of x, most significant byte first.bytes(P), where P is a point, returns bytes(0x02 + (y(P) & 1)) || bytes(x(P))5.int(x), where x is a 32-byte array, returns the 256-bit unsigned integer whose most significant byte encoding is x.lift_x(x), where x is an integer in range 0..p-1, returns the point P for which x(P) = x and y(P) is a quadratic residue modulo p, or fails if no such point existsGiven an candidate X coordinate x in the range 0..p-1, there exist either exactly two or exactly zero valid Y coordinates. If no valid Y coordinate exists, then x is not a valid X coordinate either, i.e., no point P exists for which x(P) = x. Given a candidate x, the valid Y coordinates are the square roots of c = x<sup>3</sup> + 7 mod p and they can be computed as y = ±c<sup>(p+1)/4</sup> mod p (see Quadratic residue) if they exist, which can be checked by squaring and comparing with c. Due to Euler’s criterion it then holds that c<sup>(p-1)/2</sup> = 1 mod p. The same criterion applied to y results in y<sup>(p-1)/2</sup> mod p = ±c<sup>((p+1)/4)((p-1)/2)</sup> mod p = ±1 mod p. Therefore y = +c<sup>(p+1)/4</sup> mod p is a quadratic residue and -y mod p is not.. The function lift_x(x) is equivalent to the following pseudocode:

y = c<sup>(p+1)/4</sup> mod p.c ≠ y<sup>2</sup> mod p.(r, y).point(x), where x is a 33-byte array, returns the point P for which x(P) = int(x[1:33]) and y(P) & 1 = int(x[0:1]) - 0x02), or fails if no such point exists. The function point(x) is equivalent to the following pseudocode:

x[0:1] ≠ 0x02 and x[0:1] ≠ 0x03).odd if x[0:1] = 0x03.(r, y) = lift_x(x); fail if lift_x(x) fails.odd is set and y is an even integer) or (flag odd is not set and y is an odd integer):

y = p - y.(r, y).hash(x), where x is a byte array, returns the 32-byte SHA256 hash of x.jacobi(x), where x is an integer, returns the Jacobi symbol of x / p. It is equal to x<sup>(p-1)/2</sup> mod p (Euler’s criterion)6.Input:

pk: a 33-byte arraym: a 32-byte arraysig: a 64-byte arrayThe signature is valid if and only if the algorithm below does not fail.

P = point(pk); fail if point(pk) fails.r = int(sig[0:32]); fail if r ≥ p.s = int(sig[32:64]); fail if s ≥ n.e = int(hash(bytes(r) || bytes(P) || m)) mod n.R = sG - eP.infinite(R).jacobi(y(R)) ≠ 1 or x(R) ≠ r.Input:

u of signaturespk<sub>1..u</sub>: u 33-byte arraysm<sub>1..u</sub>: u 32-byte arrayssig<sub>1..u</sub>: u 64-byte arraysAll provided signatures are valid with overwhelming probability if and only if the algorithm below does not fail.

u-1 random integers a<sub>2...u</sub> in the range 1...n-1. They are generated deterministically using a CSPRNG seeded by a cryptographic hash of all inputs of the algorithm, i.e. seed = seed_hash(pk<sub>1</sub>..pk<sub>u</sub> || m<sub>1</sub>..m<sub>u</sub> || sig<sub>1</sub>..sig<sub>u</sub> ). A safe choice is to instantiate seed_hash with SHA256 and use ChaCha20 with key seed as a CSPRNG to generate 256-bit integers, skipping integers not in the range 1...n-1.i = 1 .. u:P<sub>i</sub> = point(pk<sub>i</sub>); fail if point(pk<sub>i</sub>) fails.r = int(sig<sub>i</sub>[0:32]); fail if r ≥ p.s<sub>i</sub> = int(sig<sub>i</sub>[32:64]); fail if s<sub>i</sub> ≥ n.e<sub>i</sub> = int(hash(bytes(r) || bytes(P<sub>i</sub>) || m<sub>i</sub>)) mod n.R<sub>i</sub> = lift_x(r); fail if lift_x(r) fails.(s<sub>1</sub> + a<sub>2</sub>s<sub>2</sub> + ... + a<sub>u</sub>s<sub>u</sub>)G ≠ R<sub>1</sub> + a<sub>2</sub>R<sub>2</sub> + ... + a<sub>u</sub>R<sub>u</sub> + e<sub>1</sub>P<sub>1</sub> + (a<sub>2</sub>e<sub>2</sub>)P<sub>2</sub> + ... + (a<sub>u</sub>e<sub>u</sub>)P<sub>u</sub>.Input:

d: an integer in the range 1..n-1.m: a 32-byte arrayTo sign m for public key dG:

k' = int(hash(bytes(d) || m)) mod nNote that in general, taking the output of a hash function modulo the curve order will produce an unacceptably biased result. However, for the secp256k1 curve, the order is sufficiently close to 2<sup>256</sup> that this bias is not observable (1 - n / 2<sup>256</sup> is around 1.27 * 2<sup>-128</sup>)..k' = 0.R = k'G.k = k' if jacobi(y(R)) = 1, otherwise let k = n - k'.e = int(hash(bytes(x(R)) || bytes(dG) || m)) mod n.bytes(x(R)) || bytes((k + ed) mod n).Above deterministic derivation of R is designed specifically for this signing algorithm and may not be secure when used in other signature schemes.

For example, using the same derivation in the MuSig multi-signature scheme leaks the secret key (see the MuSig paper for details).

Note that this is not a unique signature scheme: while this algorithm will always produce the same signature for a given message and public key, k (and hence R) may be generated in other ways (such as by a CSPRNG) producing a different, but still valid, signature.

Many techniques are known for optimizing elliptic curve implementations. Several of them apply here, but are out of scope for this document. Two are listed below however, as they are relevant to the design decisions:

Jacobi symbol The function jacobi(x) is defined as above, but can be computed more efficiently using an extended GCD algorithm.

Jacobian coordinates Elliptic Curve operations can be implemented more efficiently by using Jacobian coordinates. Elliptic Curve operations implemented this way avoid many intermediate modular inverses (which are computationally expensive), and the scheme proposed in this document is in fact designed to not need any inversions at all for verification. When operating on a point P with Jacobian coordinates (x,y,z) which is not the point at infinity and for which x(P) is defined as x / z<sup>2</sup> and y(P) is defined as y / z<sup>3</sup>:

jacobi(y(P)) can be implemented as jacobi(yz mod p).x(P) ≠ r can be implemented as x ≠ z<sup>2</sup>r mod p.There are several interesting applications beyond simple signatures.

While recent academic papers claim that they are also possible with ECDSA, consensus support for Schnorr signature verification would significantly simplify the constructions.

By means of an interactive scheme such as MuSig, participants can produce a combined public key which they can jointly sign for. This allows n-of-n multisignatures which, from a verifier’s perspective, are no different from ordinary signatures, giving improved privacy and efficiency versus CHECKMULTISIG or other means.

Further, by combining Schnorr signatures with Pedersen Secret Sharing, it is possible to obtain an interactive threshold signature scheme that ensures that signatures can only be produced by arbitrary but predetermined sets of signers. For example, k-of-n threshold signatures can be realized this way. Furthermore, it is possible to replace the combination of participant keys in this scheme with MuSig, though the security of that combination still needs analysis.

Adaptor signatures can be produced by a signer by offsetting his public nonce with a known point T = tG, but not offsetting his secret nonce.

A correct signature (or partial signature, as individual signers’ contributions to a multisignature are called) on the same message with same nonce will then be equal to the adaptor signature offset by t, meaning that learning t is equivalent to learning a correct signature.

This can be used to enable atomic swaps or even general payment channels in which the atomicity of disjoint transactions is ensured using the signatures themselves, rather than Bitcoin script support. The resulting transactions will appear to verifiers to be no different from ordinary single-signer transactions, except perhaps for the inclusion of locktime refund logic.

Adaptor signatures, beyond the efficiency and privacy benefits of encoding script semantics into constant-sized signatures, have additional benefits over traditional hash-based payment channels. Specifically, the secret values t may be reblinded between hops, allowing long chains of transactions to be made atomic while even the participants cannot identify which transactions are part of the chain. Also, because the secret values are chosen at signing time, rather than key generation time, existing outputs may be repurposed for different applications without recourse to the blockchain, even multiple times.

Schnorr signatures admit a very simple blind signature construction which is a signature that a signer produces at the behest of another party without learning what he has signed.

These can for example be used in Partially Blind Atomic Swaps, a construction to enable transferring of coins, mediated by an untrusted escrow agent, without connecting the transactors in the public blockchain transaction graph.

While the traditional Schnorr blind signatures are vulnerable to Wagner’s attack, there are a number of mitigations which allow them to be usable in practice without any known attacks. Nevertheless, more analysis is required to be confident about the security of the blind signature scheme.

For development and testing purposes, we provide a collection of test vectors in CSV format and a naive but highly inefficient and non-constant time pure Python 3.7 reference implementation of the signing and verification algorithm.

The reference implementation is for demonstration purposes only and not to be used in production environments.

(e,s) instead of (R,s) (see Design above). Since we use a unique encoding of R, there is an efficiently computable bijection that maps (R, s) to (e, s), which allows to convert a successful SUF-CMA attacker for the (e, s) variant to a successful SUF-CMA attacker for the (r, s) variant (and vice-versa). Furthermore, the aforementioned proofs consider a variant of Schnorr signatures without key prefixing (see Design above), but it can be verified that the proofs are also correct for the variant with key prefixing. As a result, the aforementioned security proofs apply to the variant of Schnorr signatures proposed in this document.p is odd, negation modulo p will map even numbers to odd numbers and the other way around. This means that for a valid X coordinate, one of the corresponding Y coordinates will be even, and the other will be odd.-1 is not a quadratic residue, and the two Y coordinates corresponding to a given X coordinate are each other’s negation, this means exactly one of the two must be a quadratic residue.compressed encoding for elliptic curve points used in Bitcoin already, following section 2.3.3 of the SEC 1 standard.P on the secp256k1 curve it holds that jacobi(y(P)) ≠ 0.This document is the result of many discussions around Schnorr based signatures over the years, and had input from Johnson Lau, Greg Maxwell, Jonas Nick, Andrew Poelstra, Tim Ruffing, Rusty Russell, and Anthony Towns.